Based on fossils of their throats, tiny creatures called yunnanozoans — which lived more than half a billion years ago — have been established as a link in the emergence of vertebrates from invertebrates.

Of all the parts that make up a vertebrate, or an animal with a backbone, it was tiny ones located in the throat that made the case: yunnanozoans, animals resembling leeches that lived hundreds of millions of years ago, represent an intermediate step in the evolution of vertebrates from their spineless ancestors.

“Our research confirms yunnanozoans as the oldest known stem vertebrates,” says paleontologist, Baoyu Jiang, at Nanjing University. The finding, which Jiang’s team published in Science1, plugs a significant gap in the understanding of vertebrate evolution.

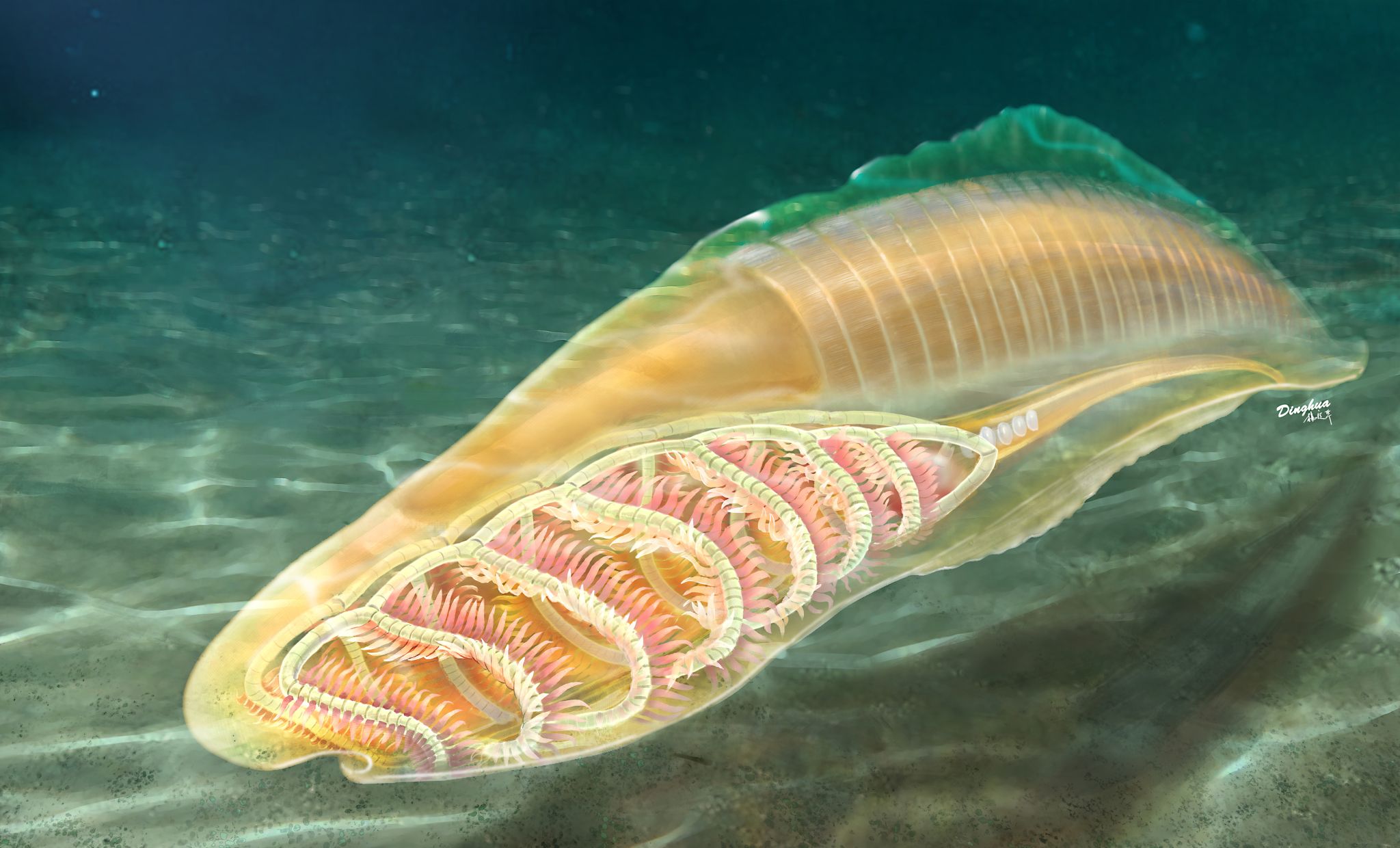

A reconstruction drawing of yunnanonzoans.

Credit: Nanjing University

Despite making up perhaps just 5% of all animal species, since the emergence of life hundreds of millions of years ago, vertebrates have evolved into a remarkable range of creatures that include fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. “Vertebrates are one of the most successful groups of animals on Earth,” says Jiang.

Yet how the very first vertebrates got their namesake — a backbone —has remained mysterious.

First vertebrates

Scientists have developed many ideas about how vertebrates might have evolved, but without much proof. “There wasn’t much evidence to show what this early vertebrate might have looked like or where it fits in the family tree of animals,” Jiang explains.

Evidence that would help to answer that question was unearthed in the 1980s from among the Chengjiang Biota — a diverse collection of extraordinary well-preserved early marine fossils from China’s Yunnan Province. In the shale deposits, paleontologists found fossils of yunnanozoans, ancient marine creatures that lived around 518 million years ago during the Cambrian Period.

Baoyu Jiang (upper right) and his team on a site of the Maotianshan Shale.

Credit: Nanjing University

Since their discovery, scientists have fiercely debated whether yunnanozoans were early vertebrates or something entirely distinct. To answer that question, Jiang directed his attention to the pharyngeal arches in yunnanozoans, essential components in the animal’s throat.

“Pharyngeal arches are building blocks located in the front part of our body, just under the brain,” Jiang explains. These structures are unique to animals with backbones and are vital for breathing and eating. In humans, they appear in embryos, being particularly visible from the fourth week of development, before slowly changing into parts of the jaw, ears, larynx, and other structures. In fish, they support the gills, enabling them to breathe underwater.

The Jiang team applied a series of high-tech analytical procedures to more than 100 specimens of yunnanozoans collected from the Maotianshan Shales, part of the Yu’anshan Formation, in Haikou town, near Kunming.

A well-preserved yunnanozoan specimen.

Credit: Nanjing University

First, they used X-ray computed microtomography to create detailed 3D images of the internal structures of the fossil yunnanozoans, which images revealed cellular chambers within the pharyngeal arches similar to the oldest-known vertebrates, demonstrating a link to vertebrates.

Decoding vertebrate origins

Next, the Jiang team explored the nature of cartilage within these arches using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

They identified fibrillin microfibrils, 12-nanometer wavy fibrils in the pharyngeal arches’ cartilage. They did not look like the thicker collagen fibrils that make up cartilage in most today’s vertebrates, but instead resembled those found in some primitive vertebrates and invertebrate chordates such as marine lancelets, demonstrating a link to invertebrates.

The researchers concluded that yunnanozoans combine the pharyngeal arches of a true vertebrate, along with a form of cartilage that only exists in primitive vertebrates and invertebrates. Evolutionarily speaking, yunnanozoans fall between invertebrates and vertebrates, and could represent an intermediate stage between them.

“Our study solves the longstanding debate on the evolutionary connection between yunnanozoans and vertebrates.” Jiang explains, “These discoveries not only hint at the structure of early vertebrates, but also shed light on the origins of crucial anatomical features such as jaws and braincases in our own evolutionary history."

Jiang’s team continue to unravel the enigma of yunnanozoans and their evolutionary relationship with vertebrates, investigating the remaining structures that could expose more detailed anatomy of ancestral vertebrates.

By studying fossils that offer snapshots of different points in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, Jiang’s team continues to reveal how vertebrates evolved, one discovery at a time.

References:

1. Tian, Q., et al, Science 377, 218-222 (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.abm2708

Source: Office of Science and Technology